Deep Arctic Time

In 1959, geologist Paul T. Walker left a bottled message in a cairn on Ward Hunt Island in the Arctic (83’N latitude), allowing its finders in 2013 to determine that a nearby glacier had retreated over 200 feet in 54 years. It is the only known time capsule in the Arctic region. Paul T. Walker didn’t know then whether the glacier was advancing or retreating. Still, he wanted a reference point that would allow future researchers in the area to provide him with important data. Sadly, the same year, he had a stroke in the field and died.

54 years later, in 2013, Walker’s time capsule was found. Per his request, biologist Warwick F. Vincent measured the distance between the cairn and the glacier, which had grown from 1.2 meters to 101.5 meters in the 54 years that had passed—because the glacier had shrunk dramatically. In the same year, in 2013, the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii reported that the daily mean CO2 concentration has surpassed 400 parts per million for the first time since measurements began in 1958, and the 5th IPCC’s assessment report confirmed that humans are the “dominant cause” of global warming.

We have gone a long way since Paul T. Walker left us a message. Since 1958, a vast planetary-scale network of satellites and in situ sensors has expanded our understanding of anthropogenic climate change and how space and deep time unfold in the region. Nowhere is climate change more evident than in the Arctic; a new study shows that the Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the rest of the world over the past 43 years.

The Arctic helps regulate the world’s temperature, so as more Arctic ice melts, the warmer our world becomes. When covered with sea ice, the Arctic Ocean reduces the absorption of solar radiation. As the sea ice melts, absorption rates increase, resulting in a positive feedback loop where the rapid pace of ocean warming further amplifies sea ice melt, contributing to even faster ocean warming. This feedback loop is largely responsible for what is known as Arctic amplification and explains why the Arctic is warming so much more than the rest of the planet.

Besides sea ice, the Arctic contains other climate components extremely sensitive to warming. One of those elements is permafrost, a frozen layer of the Earth’s surface. As temperatures rise, the topmost layer of soil that thaws each summer deepens. This, in turn, increases biological activity in the active layer resulting in the release of carbon into the atmosphere. Arctic permafrost contains enough carbon to raise global mean temperatures by more than 3℃. Should permafrost thawing accelerate, there is the potential for a runaway positive feedback process, often referred to as the permafrost carbon time bomb. Unmitigated action in the Arctic can lead to $70 trillion to the overall economic impact of climate change if the planet warms by 3°C by 2100.

The Arctic is in itself a time capsule suspending our deep geological past. We recently discovered that the Arctic Circle is home to an estimated 90 billion barrels of oil, an incredible 13% of Earth's reserves. It's also estimated to contain almost a quarter of untapped global gas resources. It’s also quite strange to think that the earth’s melting glaciers are currently pouring into the polar oceans billions and billions of small living organisms that haven’t been seen on the planet in millions of years (since this region was a tropical land). These future micro-ecologies are bringing the past to the present;

To add to this, recently, scientists have revived a giant virus isolated from Siberian permafrost, making it infectious again for the first time in 30,000 years, and we discovered the world’s oldest DNA from 2m years ago — one that could act as a genetic road map for how different species might adapt to a warmer climate. Moreover, two other bacteria species recovered from thawing permafrost were found to degrade dioxins, furans and volatile liquids, which could aid in remediating contaminated sites. Lastly, researchers found one bacterium that could survive in the cold and biodegrade oil in contaminated Arctic soil; it could take up 60% of the oil around it. This could potentially help clean up oil spills in the Arctic.

As the ice retreats, the Northwest Passage opens up, leading to new geopolitical tensions between Russia, the United States, China, and other actors jostling for influence. But unlike Antarctica, the Arctic is not a global common, with no overreaching treaty governing this region. All these factors have made the Arctic Five nations (Norway, Russia, Canada, Denmark, and the United States), as well as the three nations proximate to the Arctic Circle (Iceland, Finland, and Sweden), contemplate the probable scenarios related to the initiation of new navigational routes there. Another study found that the new shipping routes opened by melting ice in the Arctic can be 30 to 50% shorter than the Suez Canal and Panama Canal routes and can cut travel time by 14 to 20 days. Ships will thus be able to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by 24 percent, while saving money on fuel and ship wear and tear.

Arctic time capsule

I’m interested in deep time and how it relates to our collective memories and multigenerational stewardship of the planet. The rapid advancement of human civilisation has led to our ability to significantly impact the planet, altering it in ways that will affect future generations. For example, the maintenance of biodiversity, biogeochemical flows, and land-use changes all require protection over long durations to be effective. Additionally, carbon sequestration, storage and nuclear waste management demand stable institutional safeguards lasting centuries, which is longer than any of our current institutions. I’ve been reflecting on organisational principles and investigating media for transmitting information over millennia in another blog. As part of this exploration, I discovered time capsules as a storage medium for deep time.

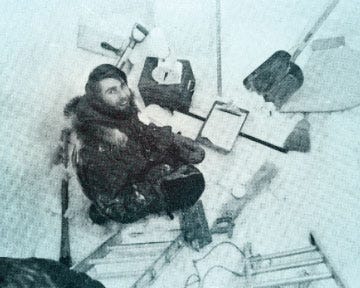

In my Arctic Circle residency, I am paying tribute to both Paul T. Walker and future generations by planting a time capsule in the Arctic, which will be opened in 35 years. My time capsule is a container that stores for posterity a selection of objects, pictures and photographs that capture our understanding and discourse of anthropogenic climate change in 2023 and will be opened in a radically different Arctic in 2055.

This time capsule aims to preserve the salient features of our history at this specific point in time. It includes printed records of our contemporary understanding of the Arctic, like:

Satellite photos of an enormous dust cloud dubbed "Godzilla" surged over the Sahara Desert due to Arctic climate change.

Pandoravirus, the oldest virus ever to have been revived, resides in the Arctic (48,500 years old)

Recent climate records of yearly temperatures over the Arctic and the entire globe

The first evidence of sponges eating ancient fossil matter in the high central Arctic.

The Arctic code Vault Tech Tree is a selection of works that describe how the world makes and uses software today.

Mammuthus primigenius mitochondrion, complete genome.

Images of how the moon could affect how much methane is released from the Arctic Ocean seafloor.

A box of hollow glass microspheres spread on young Arctic sea ice, found to increase reflectivity and halt warming.

A copy of the Saami alphabet (part of the efforts to preserve Arctic people’s languages).

A personal photo.

It will serve as a valuable reminder of one generation for another of its responsibility to steward the Arctic long term. This time capsule is stored in a historic place in Longyearbyen and is registered with the International Time Capsule Society, which will preserve its record for 35 years. The International Time Capsule Society estimates 10,000 and 15,000 time capsules worldwide, carrying messages of hope and wisdom for future generations.